Written by Dr Douglas Palmer, Museum Information Developer, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge

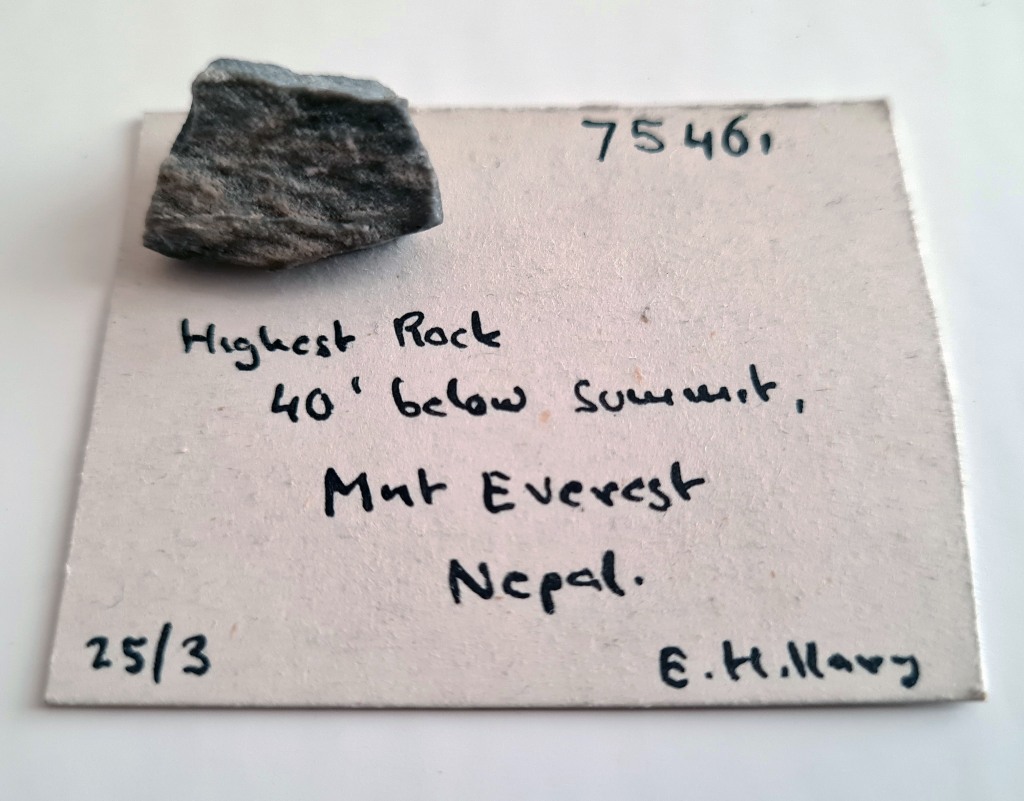

Superficially, this rock is one of the least interesting in the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences – resembling a small chip of road gravel. However, it is an unique and historic specimen, as hinted at by its original label. Hand written by the well-known Museum curator, Bertie Brighton, (1901-88) the card gives succinct details: ‘Highest rock. 40 ‘ below summit, Mnt Everest. Nepal. E. Hillary’. Whilst this information would have resonated with most British adults and schoolchildren in the late 1950s, what does it mean to the general public today?

Unravelling the backstory to the specimen’s collection and subsequent journey to the Museum has been fascinating. 70 years ago, at 11:30 am on May 29th, 1953, Tenzing Norgay, a Tibetan Sherpa and Edmund Hillary, a New Zealand beekeeper, made the first successful ascent of the highest mountain in the world.

The first successful ascent and sample collection

Since the first expedition in 1922, which was a British one, the 8,849m (29,032ft) Himalayan peak had defeated numerous attempts at the cost of many lives. However, such was the attraction of the challenge – in terms of personal ambition for mountaineers and national prestige, that by the 1950s, competing national teams had to queue to make the

attempt. By this time, the only route available to westerners was through Nepal as the Chinese controlled the Tibetan side.

In 1952 a Swiss team, including Tenzing Norgay, got within a few hundred metres of the summit. The following year, the British were to be allowed their ninth attempt and if that failed, the French had priority for the next attempt followed by the Swiss again. Such was the increasing knowledge of the mountain and improved technical assistance in the form of oxygen breathing equipment, that the British realized that the 1953 expedition was probably their last chance to be first to ‘conquer’ the mountain. As a result, the expedition was carefully planned and on a large scale. With some 400 members, there were 15 climbers, 20 Sherpas and 362 porters and was led by a 43 year old army officer and experienced alpinist Col. John Hunt.

Base Camp was established at some 5,364 m (17,598ft) on 12th April and by 21st of May, the lead climbers

had moved high up the mountain and into position for an attempt on the summit. First up were Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon, who were using closed-circuit oxygen sets. They reached 8,750 m (28,700 ft) i.e. within 100m of the South Summit but then had to give up due to problems with the oxygen sets and lack of time.

Next up on 28th May, were Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary, who had taken part in the 1951 British Reconnaissance Expedition led by Eric Shipton. Using more conventional open-circuit oxygen sets, the pair reached the snow dome summit at 11.30 am local time on May 29th.

Neither climber was a geologist and the geological nature of the rocks below their feet was probably one of the last things on their minds. Even if they had known that they were standing on 450 million year old seabed sediments originally deposited in the Southern hemisphere would they have cared when descending the mountain was just as dangerous as

climbing it?

Nevertheless, it appears that Hillary stopped just below the summit snow dome and collected a rock sample. Why did he do that – presumably someone asked him to, but who?

The British team were well aware of the significance any success would have back home in Britain, as Queen Elizabeth’s coronation was on June the 2nd. However, there was the problem of how to get the news back to London in time for the coronation. Thanks to the ingenuity of a Times reporter James Morris (later and better known as travel-writer Jan Morris), who was embedded with the team the news did reach London in time.

It was the 30th of May before Tenzing and Hilary re-joined the awaiting advance party high on the mountain. Morris was also there and immediately typed out a message ‘SNOW CONDITIONS BAD STOP ADVANCE BASE ABANDONED YESTERDAY STOP AWAITING IMPROVEMENT STOP ALL WELL’. When decoded this meant that the ‘summit of Everest reached on May 29 by Hillary and Tenzing’.

Without radio connection, the message had to be relayed by runner some 26 km to an Indian Army radio station at Namche Bazaar. From there it was relayed the Foreign Office in London where it arrived on the eve of the coronation and in time for the morning papers on Coronation Day. Some headlines put the news on an equal footing with the coronation,

the Daily Mail had : ‘THE CROWNING GLORY – EVEREST CONQUERED….Nature’s greatest prize belongs to the Queen this morning.’

In the impoverished doldrum years of post-war Britain, the Coronation was being heavily promoted as a celebration of a ‘new dawn’ and the beginning of a ‘new Elizabethan era’. Inevitably, there were some jingoistic and imperialist overtones in the reporting. Both the successful climbers were portrayed as being practically British when in fact Tenzing was Tibetan and Hillary a very proud New Zealander.

Naming of Everest

As for the mountain, which was referred to as Mount Everest in Great Britain, where did that very British sounding name come from? The Himalayan range was probably the first recognized of Earth’s major topographic features, being mentioned in a sacred Hindu text, the Rig Veda (X:121:4), dating from around 1000 BCE. Interest in Himalayan geography

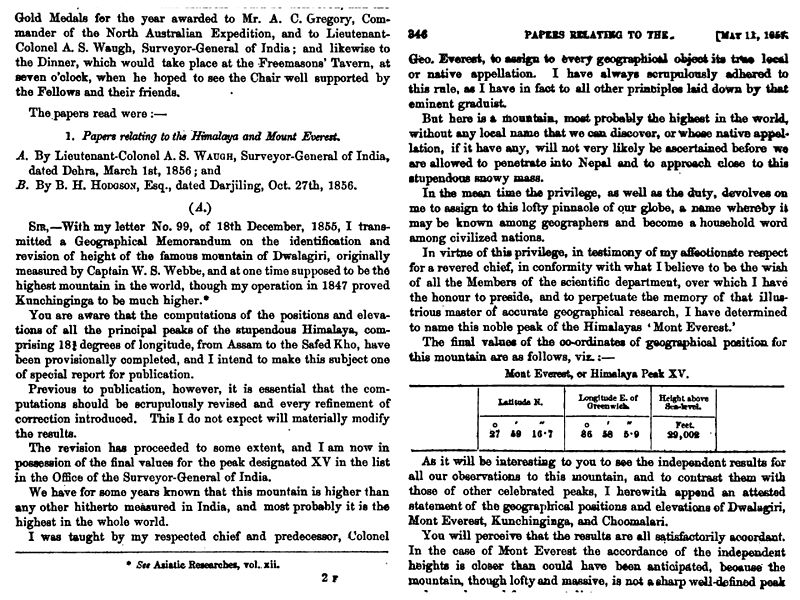

and geology began in the 19th century with the pioneering work of the British Colonial Great Trigonometrical Survey of India. They eventually provided the first estimate of 29,0002 ft for the height of the highest peak in the range, first known as Peak ‘B’ and then Peak XV. The height was obtained by instrument-based trigonometric triangulation from some 100 miles away and was remarkably accurate. The estimate was probably calculated by the Indian mathematician and Chief Computer of the Survey, Radhanath Sikdar (1813-1870).

The name Mount Everest was the result of the British colonialisation of the mountain whose Tibetan name is Chomolungma, meaning ‘Goddess Mother of the World’ and the Nepali name is Sagarmatha meaning ‘the Head of Earth touching the Heaven’. ‘Mount Everest’ was first suggested in 1856 and finally imposed in 1865 in honour of Colonel Sir George Everest (1790-1866), who was Surveyor General of India from 1830-43. Apparently, Everest himself objected to the name since he had nothing to do with the discovery of the mountain, nor was his name easily written or pronounced in Hindi. Today, the highest mountain in the world is most commonly and reasonably known by the much more ancient Nepali name Chomolungma.

But who persuaded Hillary to stop and collect a specimen from the first rock outcrop he came to, and why? The answer seems to be provided by the Sedgwick Museum catalogue, which lists the summit rock specimen as the last of 31 specimens from ‘Everest’ (Chomolungma) donated by G. Band.

Eventually, I found out that G (eorge) Band was the youngest member of Hunt’s 1953 team and a 3rd year geology student in Cambridge. There are photos of Band and Hillary which seem to indicate that they got on well. Band is the only person who would have been in a position to ask this favour of Hillary. No doubt he would have explained why it was so important to obtain a specimen of the summit rock.

Geology of Everest

From the 1920s, geologists were increasingly interested in the structure of the Himalayas and Everest in particular. What were the rocks that formed Earth’s roof and how old were they? It was generally thought that the summit rocks are sedimentary strata lying conformably on older more metamorphosed rocks. The geologist Noel Odell had previously mapped the summit pyramid as an ‘Upper Calcareous Series’ of presumed Permo-Triassic age.

Some 40 years later another geologist, Lawrence Wager, wrote that ‘it never ceases to surprise the writer that the highest point of the Earth’s surface is composed of sedimentary rocks that are relatively flat-lying and but little metamorphosed.’ Writing before the advent of plate tectonics, Wager assumed that Everest was part of the uplift of the whole range.

So the hope was that by collecting a specimen from the summit, it might be possible to determine the exact nature and age of Earth’s highest rocks. Hillary was renowned as a man of his word and if Band had asked him to collect a specimen he would have done so. Curiously there is no known written confirmation of this possible transaction, except for the Sedgwick catalogue and unfortunately George Band died in 2011 so it is not possible to verify the story.

We are not sure of when Band’s ‘Everest’ collection arrived in Cambridge, except that it must have been before 1968 when Brighton retired. The original specimen was cut to make ‘thin sections’ for detailed examination, which is why the remaining piece is so small. Although the sections revealed that the rock is an impure limestone, no age could be determined as no fossils were found.

It took several decades before geologists found that the Chomolungma summit limestones do in places contain 450 million year old fossils of Ordovician age. They are the remains of shallow tropical marine life which thrived in the Southern hemisphere equatorial waters.

The Sedgwick’s little rock conceals a big story but how to convey it to today’s public?

Two audio labels, summarising both the history of the specimen and the geology of Everest, have been installed in the Sedgwick Museum to mark the 70th anniversary of the ascent. You can listen to the labels here.

Dr Douglas Palmer

Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences

One thought on “Sampling the roof of the world: what’s in a label?”