Written by Sophia Reinisch, Amateur entomologist interested in taxonomy, life history, and evolution of Hymenoptera.

For the Geological Curators Group (GCG) Digital Morphology Workshop we were kindly invited to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) to learn about techniques of digital morphology within the palaeo sciences. The tutors for this workshop were the wonderful Duncan Murdock and Frankie Dunn who led us through several practical demonstrations as well as lecture-based content, providing insight into technical practices and current research benefits of digital reconstruction in the life sciences.

We started the day with a lecture from Duncan Murdock on an introduction to digital morphology and tomography; digital morphology being the technicalities and methodology behind visualising objects or specimens digitally, usually as three-dimensional representations. Morphology can be described as the analysis and study of form/physical characteristics. This lens often accompanies resources within taxonomical sciences, classification, and is a premise for many identification materials within the natural sciences.

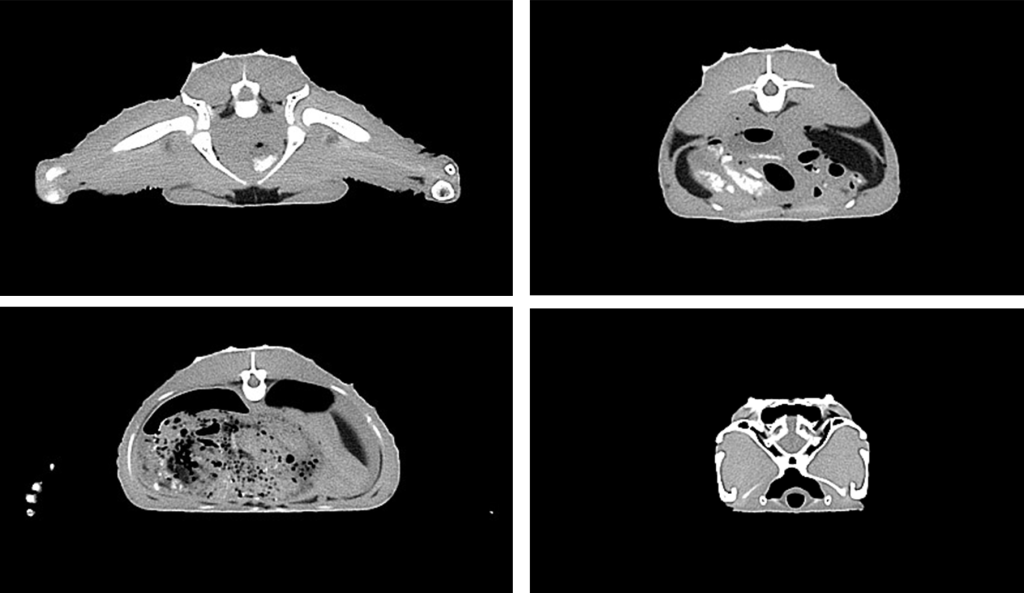

Duncan briefly outlined and introduced the group to a handful of tomographic techniques. Tomography is the reduction of an object into stacked image ‘slices’, from these it is possible to use software to reconstruct the original morphology and create a 3D model. We learnt about both destructive tomographic techniques, such as sawing the physical object, slicing and grinding, and then proceeded to non-destructive techniques with an emphasis on the uses of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI scans) and X-Ray Computed Tomography (CT scans). We discussed errors and oversights (also called artefacts) when working with such techniques, and emphasised the nuances of producing such digital resources, requiring a lot of time, patience, attention, and prior research. The lecture ended with an introduction to more accessible means of 3D model creation, and Duncan took us through surface-based methods of scanning (the result will not document the internal structure of an object or specimen) which is exemplified through technologies available on newer iPhones, as well as through laser scanning, structured light scanning and photogrammetry (the compilation of a series of photographs from around the object and layered to create a 3D model).

Frankie then took us through some of the applications of these technologies within various scientific disciplines. CT scanning is amazing in that it measures the phase of the x-ray beam passing through the object, specimen or material, a great method for tomographic data as it penetrates the matrix around a fossil and can be used to isolate and image internal structures and materials for analysis and research. My favourite example of this being the use of the CT scanner to view the internal structure of a rock from the Ediacaran, just prior to the Cambrian Explosion (around 541- 538 MYA). This scan revealed a series of tunnels made by marine invertebrates that had burrowed within the sand, and is the first ever fossilised confirmation of vertical burrowing fauna (of course an exciting one for me being an earthworm and invertebrate enthusiast!)

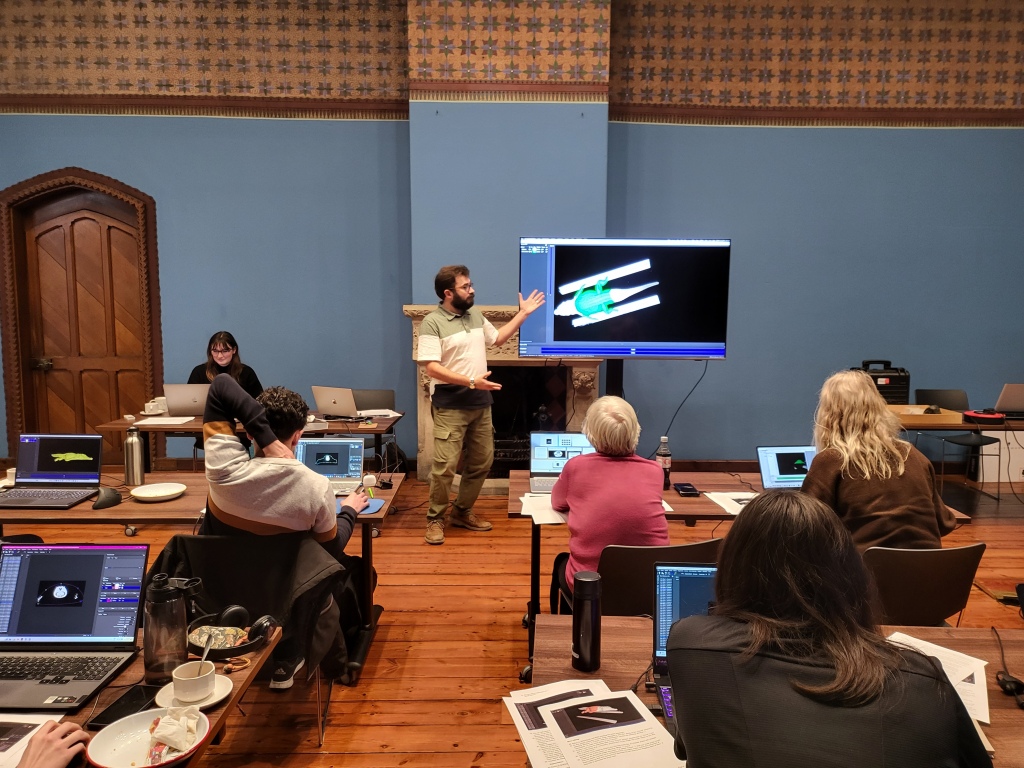

After a lunch break accompanied by a tasty sandwich and cake selection from the catering team at OUMNH, we started our practical workshop with a guide through digital morphology and the digital reconstruction of a Nile crocodile. Duncan slowly took us through this tutorial, which consisted of compiling the slices on FIJI (Fiji is just imageJ) a free image processing software, and then opening them into another free software package called SPIERS (Serial Palaeontological Image Editing and Rendering System). In SPIERS we went through a few (potentially confusing) steps in order to view the dataset and alter its proportions. After doing so we managed to isolate the bones of the crocodile from the soft tissue. Through this isolation, when proceeding to ‘hide’ the soft tissue from the 3D model, it would appear solely as the crocodile bones, the final result was particularly exciting, being able to manoeuvre the 3D model around, isolating the internal structure was the best bit!

After the practical digital work we split into three groups and alternated tasks for the rest of the workshop; One group was given some time to browse some online data sites, where there were downloadable 3D models to explore, one site was called Morphosource, a great site to browse for both the professional and non-professional.

The other group used a structured light 3D scanner called an Artec Space Spider with Duncan, this was some equipment that allowed for the imaging of a 3D object through using an iron-shaped device, the ‘iron’ has cameras installed and flashes lights while you move it around an object. The 3D image would appear on the software (on the connected laptop) and through some very easy processes (pressing a few buttons to automate some refinement) the scanned object would be edited to a clean image by filling in any blotchiness or misconfigurations.

The final group went with Frankie to the basement of the Museum. It felt like we could get lost in the maze of stores and offices but we finally found ourselves in a small room with what seemed to be a digital camera with photo stacking equipment and a desktop opposite. We were shown the amazing imaging technique of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI). This technique involves placing an object on a copy stand with a digital camera, covering the object with a dome filled with small LED lights, all connected to a programme. The dome is covered with a blackout cloth and a photo is taken of the object with each individual LED on, and the rest of the lights off (for more information, there are many YouTube tutorials available online). There is also a small black dome placed on the object which is an indication of the directionality of the light source.

Once you get all of the images, you can open a software that allows for the manipulation of the light source, and a collection of images of the object with different light directionality. This is a great technique for highlighting certain textural details of a material or object of study.

The last part of the workshop was a short but meaningful debate on the availability of open-access data, and how this may (or may not) contribute to equity within the sciences.

Frankie introduced the group to several outcomes aligned with the provisioning of data and its effect (both positive and negative) on the use of cultural and scientific materials.

One benefit of open-access data is the possibility for future replications of past studies. The ability to download and study past palaeontological material can be a great benefit to the reproduction of experiments. Another benefit is the availability of resources for non-professional scientists and palaeontologists without institutional backing. Conversations surrounding equity in science become ambiguous due to the positionality of Western institutions, and their ability to prolong the shadows of their colonial histories by exploiting materials originating in countries in the Global South. We struggle to condemn open access data, painting its applications as egalitarian and a fight for a future scientific discourse that emphasises inclusion over exclusion (or you could say to defy scientific ‘gatekeeping’). Nonetheless there needs to be conversations surrounding authority over rightful ‘owners’ (those being people, institutions, or governments of the originating location) and resource exploitation where the original proprietor’s (sometimes an institution with little funding or resources) ability to generate income from this resource is diminished by the appropriation of their data in Western institutions and countries.

Some relevant texts discussing some of these themes are: ‘Colonialism’s and postcolonialism’s fellow traveller: the collection, use and misuse of data on indigenous people’ written by Ian Pool from the journal ‘Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an agenda’ as well as ‘Rethinking Access to the Past: History and Archives in the Digital Age’ by Thomas Peace and Gillian Allen. Also ‘Postcolonial Sound Archives: Challenges and Potentials. An Introduction’ by Rasika Ajotikar and Eva-Maria Alexandra van Straaten from the journal ‘World of Music’ Volume 10.

Now to conclude, a small reflection on how I hope to apply what I learnt from this workshop into the future of my practices. I wouldn’t call myself a palaeontologist, and have learnt greatly and met lots of people from the community through GCG. My main research focuses on modern entomology, with a less explored interest in palaeo-entomology. However, I noticed how transferable all of these skills are, and how tomographic imaging is used in a plethora of natural science disciplines and research (even outside of the sciences; an example being my undergraduate dissertation in the Arts, which focussed on digital design; one technique I used was tomography and had experience with relevant software to construct digital 3D design models and 3D printing for creative projects).

There are many multifaceted applications of digital morphology across many disciplines that underpin the future of technological and scientific documentation and archival practices. It is, of course, important to keep the actual specimen when able, however a digital reproduction can serve as a fundamental contribution to current and future knowledge.